Global Europe and the Tinbergen rule

Authors

Global Europe, the EU’s proposed new instrument for external action under its 2028-2034 multiannual financial framework (MFF), embodies both an ambition and a dilemma. It aims to make EU cooperation more strategic and transformative, serving European interests while supporting global development. The question is no longer whether these goals can coexist, but how to make them work together without eroding credibility or effectiveness.

The European Commission’s proposal for a €200 billion Global Europe instrument merges several existing instruments for neighbourhood and development cooperation, pre-accession assistance and humanitarian aid. This consolidation goes hand in hand with the EU’s Global Gateway strategy, which aims to connect investment and trade with Europe’s broader geopolitical ambitions. More broadly, the proposal is part of the EU’s effort to build a new economic foreign policy, strengthening alignment and coherence between external action and internal priorities such as competitiveness, energy and economic security, migration, climate, connectivity, and access to critical raw materials.

However, this raises a fundamental question: can this single instrument truly deliver on its new dual objective of “promot[ing] stronger mutually beneficial partnerships with partner countries, contributing simultaneously to the sustainable development of partner countries and to the strategic interests of the Union”?

What is striking is that the proposal expects both objectives to be achieved simultaneously. This is new, and politically bold. It marks a departure from the usual long list of objectives attached to EU external action instruments, where priorities could often be pursued selectively or sequentially. Delivering both at once requires genuine synergies across policy areas that often compete: development, migration, trade and security. Doing so demands a clearer strategic vision, a hierarchy of objectives and governance mechanisms capable of arbitrating between them.

What is striking is that the proposal expects both objectives to be achieved simultaneously. This is new, and politically bold.

This move towards strategic interests mirrors policy shifts in many countries in the West, most clearly in the United States, where ‘national interest’ has become the guiding principle. The Global Europe proposal still refers to EU treaties, which define the primary goal of development cooperation as “the reduction and, in the long term, the eradication of poverty”. Ninety per cent of Global Europe spending must also remain compatible with the OECD/DAC definition of official development assistance, which requires aid to have “the economic development and welfare of developing countries as its main objective".

But layering a strategic objective on top of this core mandate inevitably creates tension. When trade, migration and development objectives collide, who decides which one prevails, and according to what criteria? Without clear criteria or transparent processes, there is a risk that short-term or politically dominant interests override long-term development and partnership goals. Moreover, the notion of ‘EU strategic interests’ itself remains loosely defined. Are they primarily economic, security-related, geopolitical or values-based?

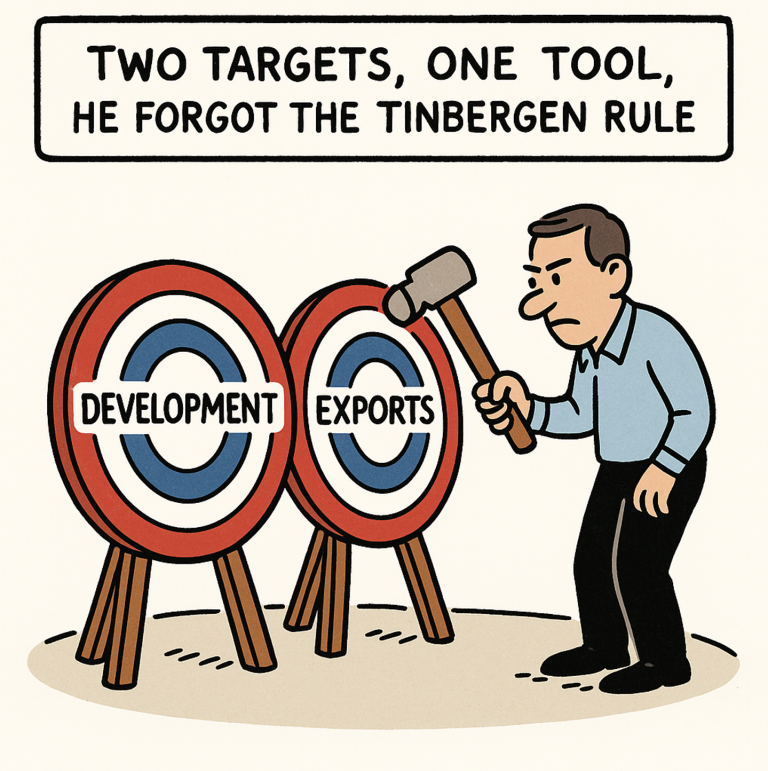

As Dutch economist and Nobel laureate Jan Tinbergen demonstrated, each independent economic policy objective requires at least one independent policy instrument to be effectively achieved. In macroeconomic policy, monetary tools address price stability, while fiscal and social policies address income distribution. This logic is not applied in development cooperation, where aid is often cast as a Swiss army knife expected to hit multiple targets: poverty, migration, trade and security – with no acknowledgement of efficiency loss.

When aid is used to achieve objectives other than its primary purpose, it almost always comes with a cost. Tied aid, for instance, links aid to the recipient's purchase of goods and services from the donor country. While this may boost the donor's exports, it also increases costs, distorts competition and weakens local markets. Trade promotion tools are a more efficient alternative. It is therefore crucial to maintain a clear separation between development finance and export credit support, as blurring the lines risks undermining development impact and reducing the effectiveness of both systems.

When aid is used to achieve objectives other than its primary purpose, it almost always comes with a cost.

The same logic applies to migration. Experience with using development aid for migration return and readmission has revealed persistent tensions. It can undermine local trust, overburden partner structures and dilute impact by forcing trade-offs between goals.

The most worrying consequence of the dual objective is its impact on geographic and thematic priorities. The language of ‘mutually beneficial partnerships’ risks becoming a cliché if it lacks concrete meaning. What looks balanced on paper may in practice tilt heavily towards European interests. It could divert aid away from where it has the greatest impact and narrow the political space for governance, gender and human rights dialogue, often perceived as holding less commercial, migration or foreign policy interest.

Reconciling EU interests with partner priorities requires identifying real complementarities between Europe’s competitiveness, security and climate goals on the one hand, and partners’ development and resilience needs on the other. It also requires differentiated and flexible engagement. This is precisely what the Global Europe instrument intends to achieve, but its success will depend on whether this flexibility is applied strategically, tailored to contexts and guided by transparent criteria. Such complementarities can exist and should be pursued deliberately. This is notably the case with climate finance and green investment, or with connectivity investments that seek to advance both Europe’s economic interests and the infrastructure needs of its partners.

The question is not whether the EU should align development cooperation with its strategic interests, but how to do so transparently and responsibly. The Tinbergen principle reminds us that distinct policy objectives require distinct tools. Even within a broad policy domain like EU external action, a consolidated framework can work, provided that the different goals and trade-offs are explicitly recognised and managed. What matters is not the number of instruments, but the clarity of purpose, the suitability of tools and the governance mechanisms to arbitrate between competing priorities.

Achieving this alignment in practice will depend on the institutional setup, specifically the programming, decision-making and accountability structures. Negotiators of the Global Europe instrument should focus less on restating ambitions and more on building the policy and governance architecture that can make this dual objective work in practice.

Negotiators of the Global Europe instrument should focus less on restating ambitions and more on building the policy and governance architecture that can make this dual objective work in practice.

First, the EU institutions should have a discussion to define the loose notion of ‘mutually beneficial partnerships’. They should clearly explain what constitutes EU strategic interests and how Global Europe interacts with the European Competitiveness Fund.

Second, the new regulation could introduce a ‘dual objective clause’ that requires programmes to specify how they balance development and strategic goals, with a public reporting system and annual debates in the Council and Parliament. A mid-term or 2030 evaluation by the European Court of Auditors, or an independent review, could also assess whether the dual objective strengthens or weakens effectiveness and partnership credibility.

Third, there is a need for greater differentiation between external financing tools. In particular, support for European private sector investment and export credit should fall primarily under the external branch of the European Competitiveness Fund. This would allow Global Europe to concentrate on development cooperation and international partnerships.

Finally, if mutually beneficial partnerships are to mean more than rhetoric, the EU should commit to measuring them in practice. This should include regular partner country feedback on how cooperation and Global Gateway investments align with their local priorities, indicators capturing tangible benefits on both sides and joint evaluations under the Team Europe framework.

Above all, the negotiation of Global Europe is a test of whether the EU can align self-interest with genuine partnership. Its success will depend not only on the size of the budget, but on the courage to manage competing interests openly and coherently.

Göran Holmqvist is a researcher affiliated with the Institute for Futures Studies and a former senior manager at the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency. Alexei Jones heads ECDPM’s EU foreign and development policy team.

The views are those of the authors and not necessarily those of ECDPM.

Our work on the MFF

Explore our dossier featuring ECDPM’s work on the new multiannual financial framework and the budget negotiations, along with insights into current and past frameworks.