The NDICI-Global Europe mid-term review exercise in sub-Saharan Africa: Lessons for the future

Authors

Philippe Van Damme analyses the mid-term review process of the NDICI-Global Europe country allocations in sub-Saharan Africa and argues that it lacked transparency and coherence, undermining the EU’s credibility and geopolitical ambitions. As preparations for the 2028-2034 long-term EU budget begin, key lessons from this exercise should inform future approaches.

Summary

In 2024, the Council of the European Union reaffirmed the EU’s ‘policy first’ ambitions to enhance its geopolitical role, and called for a transparent mid-term review of the country allocations of the EU’s neighbourhood, development and international cooperation instrument (NDICI-Global Europe). This brief analyses the review process, focusing on country allocations in sub-Saharan Africa. It argues that the review exercise was neither transparent nor well documented, and has undermined the EU’s credibility and geopolitical goals, appearing more pragmatic and opportunistic than strategic.

As preparations begin for the EU’s next multiannual financial framework (MFF), covering the 2028-2034 period, several lessons can be drawn. These include better protection of aid allocations, clearer roles for EU institutions, increased involvement of EU delegations and partner countries, and a more balanced approach to the Global Gateway strategy that considers various dimensions beyond infrastructure, such as regional integration, governance and human capital needs.

Introduction

The June 2024 Council conclusions on Europe’s new external financing instruments reaffirmed the EU’s ‘policy first’ ambitions to enhance its geopolitical role, and called for a transparent mid-term review process of the country allocations of the EU’s neighbourhood, development and international cooperation instrument (NDICI-Global Europe). However, the end result of such a review falls short of these geopolitical ambitions and transparency requirements. And while the first Von der Leyen Commission considered Africa as a geopolitical priority, the lack of inclusivity of the review exercise does not show this ambition. What lessons can be learned for the future?

Aid allocation criteria: needs versus performance

Over the last 25 years, two major shifts have characterised the EU’s development policy. First, there has been growing emphasis on political and policy considerations, reinforced by the establishment of the European External Action Service (EEAS) in 2010 and culminating in the Global strategy in 2016, which recognised that the EU’s development policy would “become more flexible and aligned with [its] strategic priorities”.

Second, there has been an increased focus – pushed by the Commission’s leadership and supported by many member states – on private investment as the engine of sustainable growth and development, with official development assistance (ODA) as oil in the engine, contributing to the creation of a more supportive investment climate. The European Fund for Sustainable Development Plus (EFSD+), an ‘innovative’ financial tool to leverage additional investments through blending and guarantees, and the Global Gateway strategy, launched in 2022 as a large-scale infrastructure and connectivity investment plan, are the operational responses to this second trend.

These shifts were meant to translate into a gradual transition from needs-driven to performance-driven aid allocations. The EU’s aid bureaucracy – particularly the European Commission’s Directorate-General for International Partnerships, DG INTPA – has resisted this trend, prioritising needs-driven allocation criteria focusing on least-developed, fragile and conflict-affected countries. Performance remains defined primarily in terms of financial absorption capacity rather than political, economic or environmental performance, which would require complex monitoring matrices and sensitive political dialogue.

These tensions between the aid bureaucracy and policymakers also emerged at the start of the budget cycle for the 2021-2027 NDICI-Global Europe.

These tensions between the aid bureaucracy and policymakers also emerged at the start of the budget cycle for the 2021-2027 NDICI-Global Europe. A compromise was reached in which the more political performance criteria – such as democratic governance, multilateral commitments and migration policies – would be assessed only during the mid-term review and integrated into an additional aid allocation tranche designed to incentivise performance. The review methodology would be developed and agreed upon simultaneously with the initial allocation (covering the period 2021-2024). This would allow for the negotiation of the baseline and results indicators during the programming phase and the integration of agreed monitoring mechanisms into regular political and policy dialogues with partner countries.

However, ongoing disagreements between services on how to conduct the programming exercise delayed the launch of the programming phase and postponed the development of the review criteria indefinitely. The European Court of Auditors (ECA) expressed concern over this situation and recommended better documentation and more rigorous application of the review allocation methodology for the three remaining years (2025-2027). It also regretted the different approaches for North and sub-Saharan Africa.

The NDICI-Global Europe mid-term review process

Contrary to what the ECA recommended, the mid-term review methodology was adopted very late, with hardly any input from the delegations and even less from various actors in partner countries. Moreover, the review was neither transparent nor well documented, and once again differentiated between North Africa – where it was delayed and results are still unknown – and sub-Saharan Africa.

We therefore tried to reconstruct the mid-term review logic for sub-Saharan Africa retrospectively, checking for statistically significant correlations between the review allocations and various potential allocation criteria. We did not find any significant correlation with traditional needs-, fragility- or conflict-related criteria, nor with traditional political and economic governance-related performance criteria. The only significant positive correlations identified were, in increasing order, with:

- UN General Assembly voting patterns on resolutions related to Ukraine and human rights violations in various countries (constructing a ‘like-mindedness index’ based on voting behaviour across a representative sample of resolutions).

- Traditional financial absorption capacity (measured as the percentage of allocated funds already committed).

- Estimated future financial absorption capacity (based on a theoretical pipeline of Global Gateway-related projects, as we could not assess its quality or credibility).

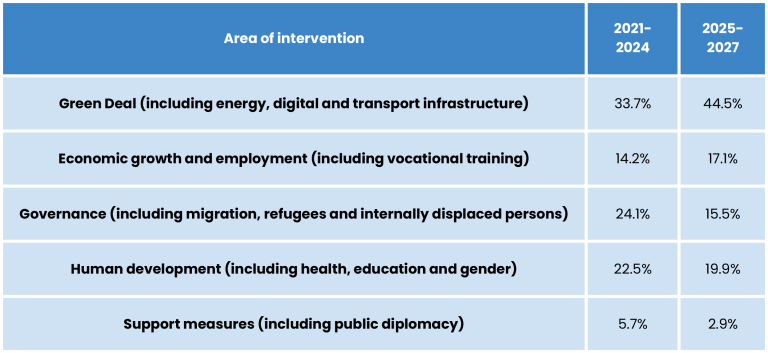

Table 1: Focus areas in programming

Source: ECDPM, based on data from the European Commission

As can be seen in table 1, the mid-term review resulted in a significant increase in allocations in support of the Green Deal. Assuming the Global Gateway pipeline is largely linked to Green Deal investment programmes, we found a strong positive correlation with the mid-term review allocations, as shown in figure 1.

Figure 1: Correlation between Green Deal – Global Gateway programming and mid-term review allocations

Analysis of the mid-term review exercise

The 2024 mid-term review exercise raises a number of concerns, in terms of substantive results and process.

First of all, the crowding-out effect of the Global Gateway strategy leads to strategic and geopolitical incoherences. The European Commission’s Directorate-General for European Civil Protection and Humanitarian Aid Operations (DG ECHO) complained that the mid-term review would lead to “dramatic and disproportionate cuts for countries in situations of crisis or fragility”, harming the EU’s geopolitical interests (including regional stability, security and migration objectives, particularly in the Sahel).

The crowding-out effect of the Global Gateway strategy leads to strategic and geopolitical incoherences.

DG INTPA refuted those concerns. However, considering a major mid-term review transfer of funds to the regional envelope in support of EFSD+, and assuming a large portion of those EFSD+ funds would benefit middle-income countries, there has indeed been a substantial decrease in funding for least-developed or low-income countries and for countries in situations of fragility, as well as for human development- and governance-related sectors. The inconsistent treatment of countries affected by coups (there was, for instance, no review allocation for Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger, contrasted with above-average allocations for Chad, Gabon or Guinea, the average increase being 45%) or of those facing deteriorating democratic or governance indicators (like Benin and Ethiopia) undermine the credibility of the review’s geopolitical approach. This is illustrated in figure 2, based on the V-dem institute democracy index.

Figure 2: Correlation between changes in democracy and mid-term review allocations

Second, the review process was highly centralised and driven by the geographic services of DG INTPA’s aid bureaucracy at headquarters, with only minimal political corrections by the EEAS, which was involved late in the process despite its mandate to coordinate the EU’s external action and its leading role in aid allocations and programming. Similarly, the delegations and partner countries were hardly involved – except for identifying a possible Global Gateway pipeline – contradicting the aid effectiveness agenda and the spirit of the partnership ‘among equals’.

Third, ODA is no longer guaranteed. Despite the NDICI-Global Europe earmarking a minimal amount of funding for sub-Saharan Africa, post-COVID inflation and the Russian war against Ukraine placed significant pressure on the EU budget. This resulted in a funding cut – without geographic safeguards – and a disproportional diversion of reserves intended for new needs and emergencies towards Ukraine and the Middle East. This sends an awkward message to the EU’s partners in Africa. Not only did the first Von der Leyen Commission present the partnership with Africa as a strategic priority but in addition, following the Russian invasion of Ukraine, EU delegations had been instructed to reassure the partner countries that there would be no change in the financial engagement with Africa.

Lessons learned

The mid-term review not only failed to respect various prior recommendations but ultimately undermined the EU’s credibility and geopolitical ambitions. As preparations begin for the EU’s next long-term budget – the multiannual financial framework (MFF) – several lessons can be drawn, at the regulatory, process and programmatic level.

First, the NDICI-Global Europe has not effectively protected aid allocations to sub-Saharan Africa. While it remains important to maintain – and even increase – financial reserves to meet unforeseen needs and emergencies in a rapidly changing and increasingly unpredictable world shaped by human or climate-induced turmoil, the rules governing access to these reserves must be tightened to prevent their inappropriate use. The European Parliament’s budgets committee, setting out its priorities for the next MFF last week, also recommended enhanced crisis-response capabilities with ring-fenced humanitarian aid.

Second, the respective roles of the various institutional partners within the EU must be clarified. As recommended by the European Parliament, that means, in the first place, reaffirming and reinforcing the steering role of the EEAS, in line with the Treaty of the European Union and its mandate. It also requires a stronger involvement of the network of EU delegations, under the unifying leadership of the EEAS-nominated head of delegation, as well as a stronger association of the European Parliament with ‘Team Europe’ to ensure alignment with the EU’s core values and long-term strategic interests.

Third, this implies that the EEAS must take the lead in the aid allocation and programming process and establish an early consensus with the Commission’s aid bureaucracy on the way forward for the entire duration of the next budget cycle, including periodic reviews. This consensus must be well documented and discussed transparently, with the European Parliament and member states, as well as with various actors in partner countries. It must include clear baselines, SMART (specific, measurable, achievable, relevant and time-bound) results indicators that are comparable across countries and over time, and clear and inclusive monitoring processes integrated into the various partnership dialogues.

Finally, the Global Gateway strategy has important geographic and sectoral distributional effects. The EFSD(+) experience also highlights a bureaucratic tendency to overestimate project maturity, the capacity to mobilise additional funding and the impact on achieving the Sustainable Development Goals. A more balanced approach to aid allocations and programming is therefore necessary.

For the self-proclaimed 360° approach to Global Gateway to be effective, it needs to include the following dimensions: (1) the infrastructure and connectivity needs (currently the main focus), (2) regional integration needs, to generate the economies of scale required to optimise investments in infrastructure, (3) governance and policy reform needs, to maximise the impact of investments, and (4) human capital needs, essential for ownership long-term sustainability of investments, as well as the quality of the partnership. The sequencing of the interventions under these four dimensions will also have to be carefully assessed, with an emphasis on human capital needs and governance issues (including support to civil society) where the reform-mindedness is limited and may jeopardise the longer-term impact of investments in infrastructure and connectivity.

To achieve its goals, the next MFF programming exercise will need to be more transparent and inclusive.

The 2024 mid-term review looked more pragmatic than principled, and more opportunistic than geopolitical, driven by a one-sided interpretation of the Global Gateway strategy. This gap between rhetoric and the reality on the ground, or even the perception of that reality, undermines the EU’s credibility and geopolitical ambitions in (sub-Saharan) Africa. To achieve its goals, the next MFF programming exercise will need to be more transparent and inclusive.

Acknowledgements and references

The views expressed in this brief are those of the author only and should not be attributed to ECDPM. All errors remain those of the author. Comments and feedback can be sent to Philippe Van Damme.

A full reference list is available in the PDF version of this brief.

Our work on the MFF

Explore our dossier featuring ECDPM’s work on the new multiannual financial framework and the budget negotiations, along with insights into current and past frameworks.