Debt reform for climate action: Demand grows louder, but will Europe respond?

The past few COPs have served as successive reminders of global climate injustice and the inability of advanced economies to deliver on their commitments to support developing countries. While the focus is on developed countries' unkept promise of USD 100 billion in climate finance per year, many developing countries are experiencing major sovereign debt vulnerabilities, further denying them the necessary means to adapt to climate change and develop their economies in a cleaner way.

Debt adjustments and reform therefore need to be a central consideration of any future global climate finance trajectory. But as Europe becomes more inward-looking, creditors and institutions are dragging their feet. For the EU, backing sovereign debt adjustments and reduction in a way that supports climate resilience and a green recovery can be an opportunity to demonstrate real leadership in a context where most initiatives are slow or ineffective. This could go a long way in strengthening the EU‘s relations with developing countries and Africa in particular, as much has been promised, but not enough has been delivered so far.

Fiscal and borrowing space for effective climate action

Developing countries are confronted with ever-growing debt vulnerabilities, which risk turning into a full-blown debt crisis. Nearly 60% of the poorest economies are in debt distress or at high risk of it. African countries experienced a threefold increase in debt servicing between 2010 and 2019, spent on average 15% of government revenue in servicing their debt in 2021, and are expected to pay around USD 242.8 billion in debt service through 2028.

At the same time, these countries are confronted with a strong appreciation of the dollar, higher inflation and tighter fiscal constraints, leaving them with limited borrowing space and compromised access to capital markets and climate finance in the form of financial instruments (loans, equity or guarantees). This contributes to the ‘great finance divide’ between developed countries that are able to respond to shocks – such as climate disasters, energy shortages and food crises – and invest in recovery, and developing countries that do not have those options.

Demand to link debt and climate action is growing…

This year’s annual meetings of the World Bank Group and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) were a missed opportunity to raise the ambition on debt reform for climate action – leaders failed to do much more than acknowledge the problem.

We have to find a way to link two problems with one solution, and the problems are climate and debt.

The IMF did make some efforts to address developing countries’ fiscal challenges, with the launch of the Food Shock Window for urgent balance-of-payment needs due to the food crisis, and the operationalisation of the Resilience and Sustainability Trust, which will help rechannel special drawing rights to help developing countries build resilience to external shocks.

At the same time, pressure from developing countries is mounting. The V20, a group of 58 climate-vulnerable nations, called for “immediate reform of the sovereign debt restructuring architecture”, and demanded to redirect debt payments to investments in clean energy transition and climate resilience.

The mechanism behind this is a debt-for-climate swap. These swaps redirect funds from unsustainable debt servicing towards domestic action, reducing indebtedness, while freeing up fiscal space for much-needed green investments.

The G7’s and V20’s decision to build the Global Shield against Climate Risks, a financial protection cooperation scheme to deal with loss and damage in the most vulnerable economies, is an important step. It emphasises that debt sustainability and ‘green and protection’ financing mechanisms should reinforce one another.

Pre-arranged funding and the efficient delivery of subsidies for insurance through the V20 Trust Fund is critical to ensure that we do not increase our debt burdens. [...] we do not ask for charity. What we need is stronger economic cooperation [...] between the developed world and the climate-vulnerable countries of the world.

Debt-for-climate swaps are not a silver bullet or an alternative to full-fledged debt restructuring. But experience – for instance in Belize – shows that they offer a way to debt relief while involving private creditors and investing in climate adaptation activities. The V20 proposals would allow some of the most climate-vulnerable economies to channel about USD 435 billion from debt servicing payments due in four years to climate action.

Several African countries – Cabo Verde, Eswatini and Kenya – are looking into debt-for-climate swaps, and the African Development Bank is exploring how it can support their implementation. The United Nations Economic Commission for Africa (UNECA) also put forward a proposal to establish a Sustainable Sovereign Debt Hub, linking debt to climate-resilient key performance indicators that would ultimately facilitate engagement on debt-for-climate swaps between debtor and creditor countries.

… but creditors drag their feet

While some creditors are open to the idea, and the IMF and the EU are examining mechanisms, proof-of-concept has been largely ad-hoc and outside of the major multilateral institutions. EU countries’ engagement in debt-for-climate swaps remains bilateral and small in scale – even though there is unique experience and capacity available.

Germany, through its public development bank KfW, is currently implementing a debt-for-climate swap with Egypt, that will finance a series of green government projects in the fields of energy, food and water, in line with Egypt’s national climate strategy.

This example also highlights another asset the EU can rely on: its financial institutions for development. These include the European Investment Bank (EIB) – the first issuer of green bonds, the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) and the Joint European Financiers for International Cooperation (JEFIC), the network of European bilateral banks and financial institutions, including AECID (Spain), AFD (France), CDP (Italy) and KfW (Germany).

A (geo)strategic instrument

Debt-for-climate swaps could be a strategic instrument for the EU and its member states. They can help assert EU leadership in the fight against climate while addressing debt – in line with European values and the policy-first principle. They also receive broad political support both at home and in partner countries. Debt-for-climate swaps are seen as an innovative mechanism, which translates into concrete projects. This can help strengthen the EU’s geopolitical weight and influence.

And, importantly, debt-for-climate-swaps generate concrete results – they follow a result-based sectoral type of approach, and allow creditors to retain some degree of ownership, while offering an opportunity for technical cooperation and capacity building.

Making debt-for-climate swaps a success

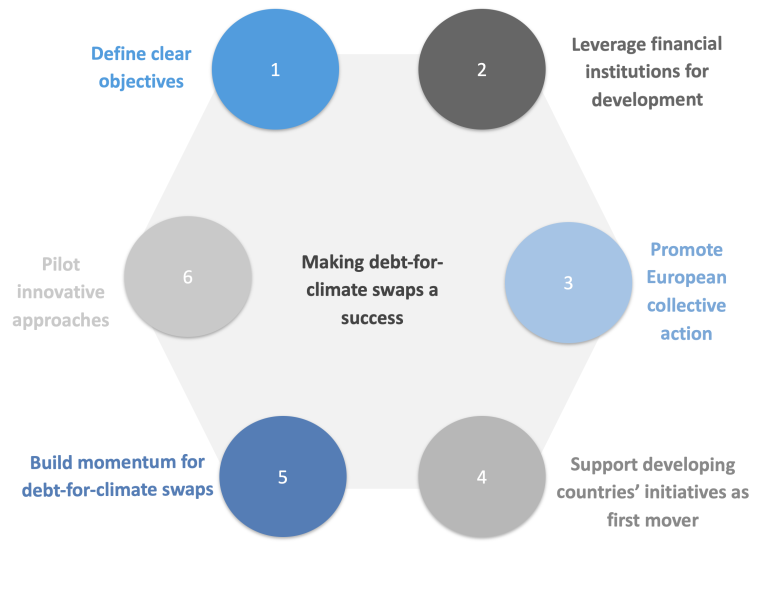

To make these debt-for-climate swaps a success, the EU should do six things:

1. Define clear (geo)strategic objectives for using debt-for-climate swaps as part of the European climate finance toolbox, in coherence with other initiatives and instruments tackling climate and debt issues.

2. Leverage financial institutions and instruments for development. The EU and its member states should tap into EIB, EBRD and the JEFIC expertise, experience and tools to reach impact at scale through debt-for-climate swaps implementation. The European Fund for Sustainable Development plus (EFSD+), following a Team Europe approach, could help mobilise de-risking mechanisms like guarantees – to facilitate private creditors' engagement, catalyse green investment and encourage the use of green, social, sustainable and sustainability-linked bonds.

3. Support developing countries’ initiatives as first movers. The EU could collectively support new endeavours driven by coalitions of developing countries, such as the V20 and initiatives like UNECA’s Sustainable Sovereign Debt Hub. Doing so as first movers, building on its status as the biggest development actor worldwide, could also attract other public and private partners.

4. Promote collective action by EU member states in the international arena. EU countries should work together – and build coalitions with other countries – to promote structural debt reforms in the IMF and the G7, G20 and V20.

5. Build momentum for debt-for-climate swaps. Ways to do this include dialogue on good practices and lessons learnt, and the development of a set of guidelines and standards for European creditors. These activities could also target other types of debt swaps, including those targeting social and sustainable investments.

6. Pilot innovative approaches to debt-for-climate swaps (as was done in Belize). This would promote participation from the private sector, create knowledge and enable further scaling-up. These initiatives should focus on swaps using a Brady-bond-like structure, which allow private and public creditors to swap their bonds at a heavy discount for these green (and credit-enhanced) bonds.

Time is against us, and any delays in financing climate action have major consequences for developing countries and progress on sustainable development. Beyond discussing climate finance commitments, leaders at COP27 should identify instruments or initiatives that can help move the debate from words to action. Debt-for-climate swaps appear clearly as one such instrument. They could help build trust between developed and developing countries, and allow them to move in the same direction.

The views are those of the author and not necessarily those of ECDPM.