After the EU-AU Summit: Inching towards just transition in Africa

The sixth EU-AU Summit was an opportunity for a candid exchange on what a just transition means in Africa, and to get concrete on financing Africa’s own decarbonisation and adaptation pathways. The rhetoric is starting to converge, but there is much to be done to make this a reality.

The final declaration calls for an energy transition that is “fair, just and equitable”, taking into account “specific and diverse orientations of the African countries with regards to access to electricity”. French president Emmanuel Macron and European Commission president Ursula von der Leyen liberally drew on their “list of concrete flagship projects” and suggested the Just Energy Transition Partnership with South Africa, which was presented at COP26, as a model to build on in countries like Senegal, Egypt and Côte d’Ivoire.

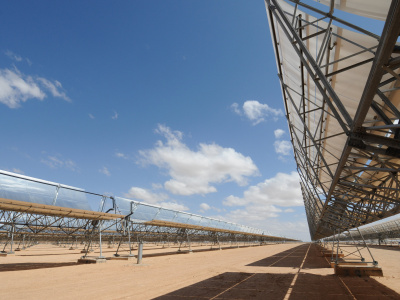

“We want to see green partnerships like the one we have with South Africa or Morocco flourish across the continent”, von der Leyen said, backed by Macron, who explained that they would seek to develop “multiple such strategic financing examples between now and COP27”.

Just transition beyond phasing out coal

The EU’s playbook is traditionally based on what it does internally. The initiative with South Africa is also not dissimilar to what it is trying to do in parts of Eastern and Southern Europe, namely weaning economies off coal.

The challenge for the AU-EU partnership will be to develop a just transition approach that is forward-looking and responds to the rapid economic development and industrialisation ambitions of African countries and societies. At the same time it should avoid shifting from one extractivist agenda to another, which is a risk with green hydrogen exports and the critical raw materials needed for renewable energy technology and storage.

A just transition for African countries requires energy infrastructure and investment in productive capacity to go hand in hand. This includes low-carbon technologies, mineral processing and manufacturing bringing quality green jobs to the African continent. This is easier said than done, and calls for a much deeper form of cooperation than the partnership and Global Gateway currently stand for.

Unresolved questions around natural gas and fossil fuels

Gas was a talking point from the moment African leaders arrived. The AU’s current Chairperson, Senegalese president Macky Sall made it clear that this is an area of divergence, even before entering the building. The reality is that ‘transition fuel’ means something different in Brussels than in Addis Ababa. The EU – largely under pressure from member states and its own fossil fuel sector – sees it as a last resort, a way to avoid worse options like coal or ageing nuclear infrastructure. African countries with gas reserves, especially those sitting on significant recently discovered resources like Mozambique and Senegal, see natural gas as a way to accelerate their economic development and industrialisation.

The final statements did not go into the gas question, nor did a mention of Africa’s “vital needs in financing fossil fuels” make the cut. The reality is that the EU will not move back to supporting fossil fuel investments externally. Even if there is a public recognition of African gas interests – if only to avoid cries of hypocrisy – EU funding and financing mechanisms (e.g. NDICI, EIB) have all but fully excluded fossil fuel projects. As the EU develops new energy flagship initiatives ahead of COP27, this is an issue that will keep coming back.

Adaptation for long-term resilience

Africa will host COP27 in November and will seek to secure a much-needed breakthrough on climate finance but also on adaptation and resilience. COP26 showed how difficult it was to bridge European and African waters, not least on the inclusion of a ‘loss and damage’ facility, and advancing the USD 100 billion global climate finance target.

The AU and EU are finding common ground in an optimistic narrative around energy and infrastructure. Yet, as the clock is ticking for COP27, they also need to urgently find new ways to address Africa’s growing adaptation needs, emphasised in the AU’s Agenda 2063 and more recently also in the draft AU Climate Change and Resilient Development Strategy (2022-2032).

The partnership will need to address the disincentives for mobilising additional adaptation finance, such as the high risks entailed, indirect returns on investment and the long-term timelines. Insufficient adaptation is also intricately linked to conflicts. If not properly addressed, peace-building efforts in the Sahel risk being incomplete and ineffective in the long run.

Managing the spillovers of European transition

The EU used the summit to market its Global Gateway, with the promise of finance for priority infrastructure dominating the conversation. Green transition in Africa and Europe, however, is linked by more than a shortage of finance from north to south.

As the EU transforms its economy and consumption patterns this will have a significant effect on trade, ranging from fossil fuels to raw materials and agricultural products. The EU’s carbon border adjustment mechanism, for example, was conspicuously absent from the public discourse on both sides, as were the respective positions and divergences in multilateral climate negotiations. For a renewed partnership to work for just transition, it will eventually need to look beyond the traditional tools of the trade.

“On a du travail”

At the closing ceremony, von der Leyen told the AU’s chairperson Moussa Faki “we have work to do”. This can go two ways. The easy option is going back home and managing projects, strengthening the bureaucratic follow-up in the hope of building some evidence to back up the new narrative. The more difficult one is working long-term, and producing a truly integrated green transition between the two continents, not just differentiating timelines, but creating the conditions for green industrialisation, innovation and long-term cooperation between continents, while stepping up efforts on adaptation. Infrastructure finance is a key ingredient of this, but one that needs to be completed with significant domestic reforms, skills and technology transfer and diplomatic efforts.

The views are those of the authors and not necessarily those of ECDPM.