Indigenous business for regional dynamics in Africa

Business transformation from rent-seekers to ‘force for good’?

Until recently, any suggestion that large-scale firms indigenous to Africa existed (except in South Africa) would have been heresy to a world used to an Africa most in need of salvation from poverty, war and famine, starving children, tyrants and warlords. While many of these pathologies still persist, the regional landscape is changing, thanks to home-grown businesses that consider Africa and its developmental needs as the centerpiece of their investment decisions. Their successes have recently been profiled in business and general interest commentaries as a major contributor to the ‘Africa rising’ narrative. The question then is whether these indigenous entrepreneurs are capable of constructing a regional identity and framing the values, norms and ideas that could change the way the African region works. In other world regions, business as part of civil society is deeply involved in the regionalisation process, whereas their African counterparts are overwhelmingly portrayed as merely rent-seeking and, therefore, incapable of policy engagement beyond selfish interests. Recent studies have challenged this over-generalisation, documenting ways African entrepreneurs have forged effective policy coalitions for better governance, including acting upon principled beliefs about regional identity as a group or by leading actors to be ‘a force for good.’ Earlier studies also missed the role of business groups (e.g. the Federation of West African Chambers of Commerce) in the negotiations that culminated in the formation of regional organisations like the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) and the new East African Community.

Regional socialisation

The regional policy role of African business is less about persuading states to adopt particular policies or holding states accountable, and more about the regional socialisation effects of their activities that frame issues and influence the choices of political decision-makers and other non-state actors. In other words, African regional dynamics are being shaped by both states and the ‘private authority’ of business and other non-state actors. Private authority refers to “the ability of private actors to establish rules and standards of behavior across borders that end up as being recognised and implemented by agents who never formally delegated their sovereign rights to the bodies in charge of their definition and implementation” (Graz 2012: 1). The effectiveness of regional integration depends on states and non-state actors partnering to develop new discourse, ideas, and norms within international institutions. Among the non-state actors forging new regional dynamics in Africa are indigenous entrepreneurs whose profit motive is shaped by the sense of place and belongingness to lead efforts to resuscitate Africa from development failures that decades of ‘dead aid’ and charity could not prevent. Most of these entrepreneurs emerged in the aftermath of the economic crisis and structural adjustment programmes of the 1970s and 1980s that led to the liberalisation of African economies. Foreign businesses pulled out, leaving Africans to fill the vacuum. Mr Tony O. Elumelu, former CEO of United Bank for Africa, coined the term, ‘Africapitalism’ in 2010 to express this pan-African ‘business patriotism’:

The answer to Africa’s development challenge is in the hands of Africans - not Americans, Europeans, or Chinese. The answer will not come from Development Bank initiatives, aid incentives, or relief programs. And the goodwill of others, however well intentioned, will never be enough to empower our industries…What we need are more capitalists with a passion for Africa. What we need are ‘Africapitalists’.

African governments soon warmed up to indigenous business as partners in long-term economic growth and sustainable development; while regional organisations - seeking to shore up their democratic credentials - opened up limited spaces for regional engagement by business and other civil society organisations. The result is a ‘new regionalism,’ a social project co-constructed and legitimated by multi-stakeholder actors. This perspective of regionalism contrasts with the neoliberal simplification of globalisation as the singular force inexorably leading to global convergence of regional economic thought and policies. Discussed below are two policy domains drawn from West Africa, namely (i) industrial and investment policies and infrastructure development, and (ii) private sector-led financial integration, that demonstrate the role of business in the unfolding drama of new regionalism in Africa.Industrial and investment policies, and infrastructure development

Infrastructure investment in Africa has risen, especially since 2006, so much that the World Bank attributed more than half of the region’s recent improved growth performance to infrastructure. According to the African Development Bank president, Akinwumi Adesina:

As we open up Africa with high quality regional infrastructure - especially rail, transnational highways, information and communications, air and maritime transport - Africa will witness a phenomenal boost in intra-African and global trade; the entrepreneurial spirit of small and large businesses, and millions of our young people, will be unleashed.

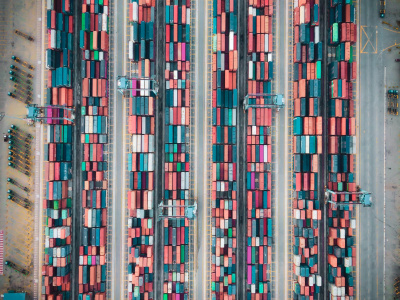

These sentiments capture the wide agreement about the positive relationship between adequate infrastructure provision and economic growth and regional development. The under-provision of infrastructure, however, increases costs to businesses, and makes industrialisation and investments unprofitable. In West Africa, business has used national and regional forums, particularly the biennial West African Industrial Forum established in the mid-1990s, as platforms to pressure governments to make the region more business-friendly and to promote regional industrial investments. Their West African Industrial Master Plan that identified strategies for stimulating regional economic development and external investment was adopted by ECOWAS in 2001. Like many ECOWAS policies, however, it was never implemented, partly because of the region’s inability to attract investment capital to the identified projects. Consequently, in 2012, representatives of business and the ECOWAS Commission developed an ECOWAS Investment Code and Policy which was legalised by the organisation in 2014 and strengthened with a regional Competitions Act and regional and national councils for the ECOWAS Common Investment Market. The ECOWAS Commission has also facilitated the formation of, and partnered with, several regional business groups on a wide range of projects, including tackling the problem of infrastructure drag on regional integration. One example is the Lomé-based ASKY Airlines established in 2009 as a joint enterprise by ECOWAS and multinational business groups as a successor to the multinational Air Afrique that collapsed in 2002. The airline currently serves 22 intra-Africa destinations; carries 10,000 passengers weekly; and partners with intra-African postal and passenger services which hitherto passed through Europe before reaching their African destinations. Similarly, in 2009, a US$60 million regional shipping company called Sealink was established in Dakar by a consortium of business associations in West and Central Africa in partnership with state agencies, ECOWAS Commission, Francophone West African Development Bank, and African Development Bank. NEPAD Business Groups have also become strong advocates for a liberalised market to drive sustainable development.Business and financial sector integration

The clearest evidence of the impact of business on Africa’s regional dynamics is the ‘private authority’ exercised by leading banks across the region. Leading the charge is Ecobank Transnational Inc. or ‘the Ecobank Group’, a pan-African financial institution whose dual-mission - commitment to economic prosperity and social wealth - has had demonstrable socialisation effects on the regional identity of Africa’s major banks, governments and other non-state actors. The Ecobank Group was founded in October 1985 in Lomé, Togo, as a private sector regional bank initiative led by the Federation of West African Chambers of Commerce and Industry supported by ECOWAS. It commenced operations in 1988 with an authorised capital of US$100 million and paid up capital of US$32 million, raised from over 1,500 individuals and institutions from across West Africa. At the time, there were hardly any commercial banks owned and managed entirely by the African private sector because the industry was dominated by foreign and state-owned banks. Due to severe economic austerity, foreign banks like Barclays and Citibank pulled out of the region. The audacity to believe that this fledgling bank would fill the vacuum left by foreign banks, and also champion a pan-African vision of bridging the differences and mistrust between the French and English speaking countries in the region, seemed irrational at the time. During its 20th anniversary in 2008, the Group CEO re-stated the bank’s mission as follows:

We have a dual mission, a commercial mission which is to make a return and run a world-class African bank. We also have another mission, which is equally important, and that is the economic and financial integration of Africa. We are positive on Africa and Africans and it is our responsibility to build African capacity and go where others might fear to tread so that we can encourage them to join us [Ecobank 2008:2;].

Today, Ecobank is one of the few genuinely pan-African companies of scale, and Africa’s sixth largest full-service regional bank. The Group, which is now owned by more than 600,000 local and international institutional and individual shareholders, is probably West Africa’s first multinational corporation with subsidiaries and branches in 39 West, Central, and Southern African countries, as well as branches in major world financial capitals. By 2015, its 19,565 multinational employees in 1,305 global branch networks and offices made Ecobank the largest employer of labour in the financial sector industry in Middle Africa. In 2015, they managed revenue of US$4.28 billion, net income of US$398 million, total assets and equity of US$40 billion and US$6.65 billion respectively, and 10 million customers.Integrative and regional socialisation effects

Ecobank’s pan-African vision led it to pioneer the provision of formal banking and financial solutions to some of the most underserved African countries, increasing the level of credit available to businesses and households, especially cross-border traders. More than any of Africa’s 500 banks, it has increased financing for critical sectors, such as agribusiness, education, health, housing, and infrastructure (shunned by many full-service, especially foreign-affiliated private sector banks) to more effectively increase regional impact. In 2011, Ecobank was recognised by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation as ‘a force for good’ and contracted to manage the Foundation’s US$6 million Financial Services for the Poor’s grant initiative targeting 10 million low-cost savings accounts in rural and poor neighborhoods in Africa. Perhaps Ecobank’s most integrative exercise of private authority occurred in 2001 when it became the sole issuer/regulator of a regional health insurance scheme, and (since 1998) the primary issuer of ECOWAS traveler’s checks and complementary ECOWAS Travel Certificate, presently in circulation in eight member states, to its customers. These instruments were introduced to implement the 1978 ECOWAS Protocol on Free Movement of People and Goods. About 50% of the estimated 4.5 million of the region’s cross-border travelers do not have identity and travel documents, making them easy prey for bribery and extortion by border control officials. Ecobank therefore is not just a firm; it epitomises the pan-African values driving regional integration in Africa. As the bank itself stated in 2008, “Africa is experiencing positive change. Ecobank is part of that change. We already feel part and parcel of the renaissance and growth that is taking place on the continent. Ecobankers are ardent believers in Africa. As we say, Ecobank does not have a strategy for Africa. Africa is our strategy”. Other (mostly Nigerian) banks rapidly expanded cross-border, acquiring formerly government-controlled banks and other financial institutions, and similarly (re)defined their identities. The Ecobank story influenced Mr Elumelu’s transformation of United Bank for Africa into one of Africa’s biggest multinational banks anchored on his ‘Africapitalism’ philosophy which has since captured the imagination of many African entrepreneurs to refocus their minds on what it means to be African in Africa. Even South Africa’s Barclays Africa Bank sold off its global operations and focused more on becoming an African bank after it had been burned badly by its global exposure during the 2008 global financial crisis. It has not wavered on its ‘vote for Africa’ even after Barclays Bank, its UK parent, divested its African interests earlier in 2016. The emergence of relatively strong cross-border banks also strengthened their capacity for cross-border policy interventions to deepen financial integration. For example, an emboldened West African Bankers Association recently created new institutions such as the West Africa Interbank Payment System and the West African Clearing House to enable regional banks to establish intra-regional letters of credit to facilitate intra-regional trade, instead of the prevailing tripartite arrangements with banks in Europe and America.

Sustainability of business role in regional dynamics

Significantly, commitment to pan-African identity does not appear to have hurt the profit mission of region-centric banks and industrial and infrastructure investors. For example, since 2007, Ecobank has garnered numerous local and international awards for its unparalleled reach in Africa, especially providing the banking infrastructure for Africa’s rising middle class. It won the 2016 Financial Inclusion award while its CEO won the 2015 African Banker of the Year award, both from the African Development Bank. However, between 2012 and 2014, South African and Qatari investors acquired 52.8% interest in Ecobank. Hitherto its largest shareholder had been ECOWAS Bank for Investment and Development (formerly ECOWAS Fund), the development finance arm of ECOWAS whose initial start-up capital of US$10 million was provided by the Nigerian government. The changed ownership of Ecobank and recent revelations of discretionary budgetary and tax rents granted to some multinational ‘Africapitalist’ firms that drained the treasury and drove hundreds of other entrepreneurs out of business in some of Africa’s largest economies amplify concerns about the ‘sovereign’ limits and legitimacy of non-democratic private authority as leaders of regional integration. Future empirical studies should help establish how truly different ‘Africapitalist’ firms are from their rent-seeking cousins. Moreover, greater integration in the global economy may complicate the dual-mission commitments of African business and by extension their capacity to create social capital and advocate for good regional governance. Thus, whether or not the Ecobanks of Africa will continue to retain their regional identity and regional socialisation effects will be interesting to watch going forward. References 1. BCG. 2010. The African Challengers: Global Competitors Emerge From the Overlooked Continent (Boston: Boston Consulting Group). 2. Ecobank. 2008. “Ecobank Group Celebrates Landmark 20th Anniversary,” Ecobank Newsletter, November 11. 3. Economist. 2014. The Rise of Africapitalism, The Economist, vol. 413, 22 November (Supplement), p. 84. 4. Elumelu, T. O. 2013. ‘Africapitalists’ Hold the Key to Africa’s Future, New African, No. 528 (May), p. 50. 5. Graz, J-C. 2012. Private Regulation in the World Economy, Academic Foresights, No. 3 (January-March). Available at: http://www.academic-foresights.com/Private_Regulation.html; accessed 25 August 2014. About the author Prof. Okechukwu C. Iheduru is a Professor of Political Science in the School of Politics and Global Studies and Thunderbird School of Global Management at Arizona State University, USA.

This article was published in GREAT Insights Volume 5, Issue 4 (July/August 2016).