New year, new aspirations for Europe-Africa relations?

Ursula von der Leyen, president of the new European Commission, chose to visit the African Union (AU) headquarters for her first official trip outside of Europe – this has been described as sending a strong political message. She has made it clear that the European Union (EU) wants to establish greater political, economic and investment opportunities between Europe and Africa, and move towards a partnership of equals beyond the donor-recipient relationship.

Although talking about a more balanced partnership between the EU and the AU is not new, changing internal dynamics, especially in Africa, suggest that maybe this time is different. These dynamics range from evolutions in regional communities, trade, migration and governance, to increased African relations with a host of other international partners and donors, like China and Russia. The need to cooperate will only continue to rise with climate change, fragility and related instability. Future AU-EU partnerships will need to be approached with a new lens – one which takes account of the sea-change in Africa’s internal dynamics.

A major issue with the Africa-Europe partnership has always been follow-up on aspirations and priorities. There have been action plans and lots of processes developed in the past, but with Africa making itself more assertive and unified, the partnership with the EU might move from being just aspirational to more transformative.

A long-standing ‘partnership’?

The relationship between EU and African states has historically been shaped by a European pursuit of interests around influence, wealth, economic growth, power and politics. This particularly relates to a history of colonialism and the donor-recipient nature of the relationship.

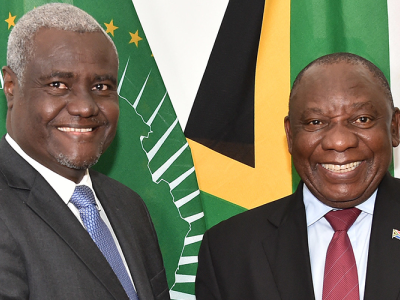

However, contemporary relations between the EU and Africa have evolved in the context of various formal and institutional instruments, ministerial meetings and the EU-Africa (now EU-AU) summits. Between 2000 and 2019, five summits were held both in Africa and Europe. These summits have been the main carefully orchestrated diplomatic forum focusing on dialogues, stock taking and the adoption of political commitments to establish deeper common priorities for the future of the AU-EU partnership.

So far, the partnership has led to several strategies, such as the Joint Africa-EU Strategy (JAES) Action Plan adopted at the summit in Lisbon in 2007, and the identification of future areas of cooperation and collaboration. These have led, for example, to increased support for the African Peace and Security Architecture to address peace and security challenges on the African continent, training for election observers, mobilisation of financing for infrastructure projects, creation of a diaspora network, investments in sustainable energy services, and promotion of science and technology.

Nevertheless, the relationship between the two groups is still characterised by asymmetry. The EU has been faulted for unilaterally designing approaches and setting the agenda with little or no involvement of African actors, such as the Africa-Europe Alliance for sustainable investment and jobs, and implementing overlapping and competing frameworks with its member states – including the EU External Investment Plan, the German Marshall Plan with Africa, France’s renewed strategy for Africa’s development, Ireland’s Strategy for Africa to 2025, and the Austrian Development Cooperation with Africa.

Further, when it comes to negotiations around the post-Cotonou Partnership Agreement, due to expire this year, the EU is seen as prioritising the grouping of (Sub-Saharan) African, Caribbean and Pacific (ACP) countries, which favours a rather traditional aid-driven north-south partnership, rather than the AU and the regional economic communities (RECs).

African states broadening their partnerships

In the background of AU-EU relations, several other major economies have been increasing their trade, investment and economic cooperation with African states. For example, foreign direct investment from China to Africa rose by 11% to US$46bn in 2018. Notably, this growing influence of China in Africa has included the adoption of China’s African Policy and increased participation of African heads of state and government at the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC). Four African presidents attended the first ministerial conference of FOCAC in 2000, compared to 51 African leaders in 2018.

Russia also held its first-ever summit with Africa last year, with high-level representatives from all 54 African states, of whom 45 were heads of state. The summit resulted in the adoption of a declaration towards more significant political, security, trade and economic, legal, scientific, technical, humanitarian, and information and environmental protection.

For Africa, these ’emerging players’ reduce the appeal of ‘traditional’ Western donors, the more so as China and Russia tend to have less explicit interest in intervening in their domestic policies. This may also change what African countries seek from their partnerships with Europe. The EU now has to compete with other key entrants entrenching long-lasting collective dialogue and practical economic and political institutional cooperation with African states.

Africa’s changing internal context

All 54 AU member states have emphasised the need for greater unity to speak with one voice in the international arena and moves towards a change of mentality and commitment for the continent to work together.

The AU has, for example, emphasised the seven aspirations of Africa’s Agenda 2063, the blueprint for transforming Africa into a global powerhouse of the future. The AU has managed to make progress on some of its flagship projects under Agenda 2063 – for instance, the launch of the operational phase of the landmark Africa Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA), which when implemented will be the world’s largest free trade area since the formation of the World Trade Organization.

The AU has also adopted the AU Free Movement Protocol and a draft plan of action. African leaders also decided that AU institutional reforms were urgent and necessary. To this end, in July 2016, the African heads of state and government made a historic decision and adopted the implementation of a 0.2% levy on eligible imports into the continent to finance the AU and bring about sustainable, predictable, equitable and accountable financing. Financing the AU has been a persistent problem since its formation with a high dependency on external donors that has caused concerns about ‘ownership’ of agenda.

Though these developments undoubtedly face implementation challenges, the progress made and momentum built up is already an achievement. It might help Africa gain a stronger, more assertive negotiating power. At the very least, it also makes it more difficult to ignore the role that the AU is expected to play as representative of all African member states within the AU-EU partnership in driving and achieving inclusive economic growth and development.

Nonetheless, the EU remains Africa’s most significant trade-in goods partner for both exports (36%) and imports (33%) and to date, the EU is the AU’s biggest donor, providing money, technical assistance and in-kind donations.

An opportunity for greater convergence of the AU-EU partnership agenda?

A more significant role of international players in African countries and uptake of more internal processes in Africa is not necessarily a blow to the partnership with the EU. In fact, the AU’s focus on internal issues creates opportunities for more mutually beneficial collaborations and agenda-setting – resulting in a partnership that is, if not equal, at least more respectful.

Africa, in speaking with one voice, can engage in more intensive discussions on the nitty-gritty of what must be included and avoided in future summits to build stronger partnerships with the EU and other external partners. Further, the AU’s attempts at being gradually more financially independent through the introduction of the 0.2% levy, though not a quick fix or stand-alone reform area, will enable it to take more ownership of the agenda.

This means that we are likely to see the AU continue to step up and try to gain more bargaining power in its partnership with the EU to move from the prism of development aid recipient. Though follow-ups to past summits have generally been quite limited, the growing urgency for cooperation and changing contexts mean that the sixth EU-AU summit, slated for late 2020, may be an opportunity for dialogue and partnership that is more clearly based on mutual benefits.

The views are those of the author and not necessarily those of ECDPM.