Europe and the post-2030 agenda: A call for action

The new year started with a bang, and not a pleasant one for multilateralism, marked by Trump-led US action in Venezuela and threats to Greenland. Less headline-grabbing was the White House announcement that the US would withdraw from a further 66 international organisations, mostly UN agencies, although the picture was actually a bit more nuanced.

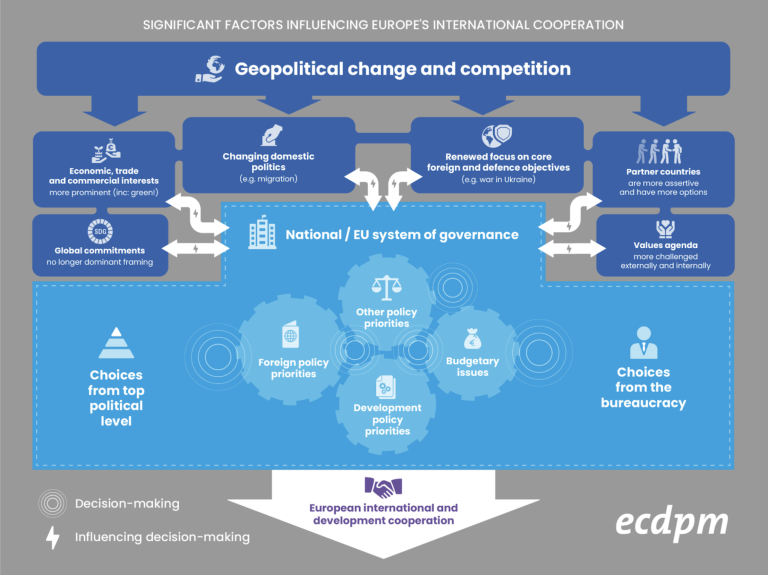

In this context, talking of the post-2030 Sustainable Development Agenda might seem slightly ridiculous. ECDPM research has indicated that the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) are no longer driving Europe’s international cooperation priorities (see diagram 1). Yet the future global sustainable development agenda post-2030 merits attention in 2026 precisely because of international volatility and the dramatic changing of global order.

Europe's strategic and coordinated engagement on a post-2030 Sustainable Development Agenda would pay geopolitical as well as global sustainable developmental dividends. Common language and common development goals, and the process to derive them are needed to inform national and foreign policy, investment decisions, planning processes and the achievement of global public goods.

What’s really driving Europe’s international cooperation today… it's not global commitments…

Lest we forget in these febrile times, the SDGs were an unprecedented global deal meant to make everyone on the planet safer and more prosperous over the long term, applicable in Europe as well as countries across the world. While hardly irrelevant, the agenda is currently widely off-track. Yet 2026 is precisely the year when those who care about the state of the planet, global solidarity and some form of functional multilateralism need to start doing some serious homework. The global agenda for sustainable development formally ends in 2030. The current state of global politics shows there is far from a guarantee that anything will replace it.

While formal deliberations on a post-2030 sustainable development agenda are likely to start at the UN in September 2027, serious engagement will depend on early preparation by thought leaders, knowledge institutes, official actors and foreign ministries, including efforts to engage partners beyond Europe. That work needs to begin in 2026 because this is the pre-official negotiation phase where ideas, goals, targets and indicators solidify and the realms and parameters of the possible are explored before the more structured diplomatic process begins.

2026 is precisely the year when those who care about the state of the planet, global solidarity and some form of functional multilateralism need to start doing some serious homework

Odds are stacked against thinking about a future post-2030 sustainable development agenda

At first glance, 2026 appears to be the worst possible moment to do so. The list of global unfavourable circumstances is long:

-

A broader crisis of legitimacy in multilateralism and the return of naked ‘might is right’ politics, led by a US that is actively hostile not only to multilateralism in general but to the 2030 Agenda in particular.

-

A massive funding, effectiveness and legitimacy crisis in the UN system that is absorbing intellectual, diplomatic and administrative energy that, despite the UN80 reform agenda, is leaving little space for forward-looking thinking on a post-2030 agenda.

-

A sense within much of the knowledge community that the high-water mark of multilateralism was the agreement of 193 countries to the SDGs in 2015, a moment that, by 2026, feels like it belongs to another era.

-

Despite improving millions of lives, a depressing lack of progress on the SDGs themselves, sapping momentum as targets appear increasingly out of reach.

-

The broad, inclusive, solidarist and often technical language of Agenda 2030 now feels deeply at odds with both the politics of the day and the logic of social-media-driven communication.

In a global order that is being rapidly remade, Europe’s absence is not cost-neutral.

Europe’s indifference and pivot away from the SDGs risks being costly

There has been a steady fading of the Sustainable Development Agenda as either a guiding compass or even a meaningful reference point for national development planning and international development policy in Europe. Amongst the drivers of European indifference are:

-

Russia’s war against Ukraine continues to drain diplomatic attention and financial resources, including those for sustainable development, with no end in sight.

-

Europe has struggled to mobilise credible multilateral leadership or to defend convincingly the ‘rules-based order’ it routinely invokes, from Gaza to Sudan and Greenland, this failure has been painfully evident.

-

A narrow focus on competitiveness and (hard) security that is incapable of effectively linking these priorities to effective multilateralism or Agenda 2030 in practice.

-

Significant, often hurried and ill executed massive cuts to European official development assistance, undermining not only SDG implementation but also the intellectual architecture, knowledge institutes, civil society and multilateral organisations, required to nourish and sustain it.

While European political leaders frequently speak about a changing world and the growing importance of geopolitics, they appear to have dramatically underpriced the cost of failing to invest in effective multilateralism and preparation for a post-2030 Sustainable Development framework. In a global order that is being rapidly remade, Europe’s absence is not cost-neutral. It is a step back in global responsibility and influence and a missed opportunity to find and help define common reference points with the rest of the world. Europe, the EU and individual European countries did play a key role in the setting up of SDGs in 2015, particularly around the climate-related targets and the peace, justice and strong institutions goal, so there is history and experience to draw from even if circumstances have changed markedly.

Other powers are not waiting

Other global and middle powers are not standing still. What is striking is that, unlike the US, many are not rhetorically withdrawing from multilateralism or rejecting its language. Instead, they are actively reframing how their approaches support sustainable development and multilateral cooperation. While this is not done selflessly, it shows that other players very much view reference to and association with multilateralism, global norms and the Agenda 2030 as still being in their interests.

Two examples illustrate this trend. China’s Global Development Initiative, launched by President Xi Jinping himself in 2021, is careful to note alignment with Agenda 2030 while introducing its own priorities and framing, and is part of a wider agenda to shape global governance and its priorities. More recently, the United Arab Emirate’s XDGs to 2045 agenda, first announced in 2023, shows the political advantage of being first-mover to articulate a future global development vision. Yet, the UAE is also careful to talk about the importance of process and the necessity of building on the SDGs. They aren’t the only ones across the world thinking about new visions. Many actors view shifting global dynamics and US retrenchment from multilateralism not solely as a threat, but as an opportunity.

So what are the scenarios for the post-2030 agenda?

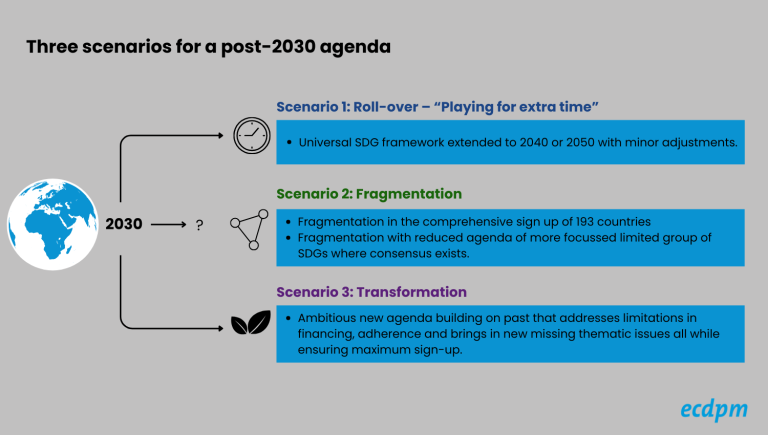

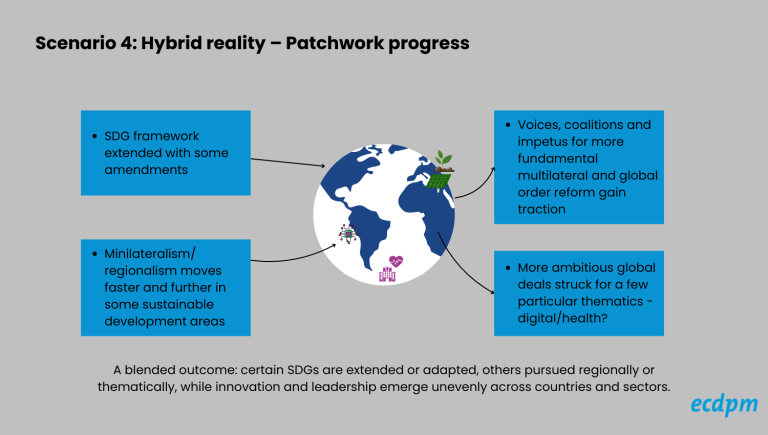

The scenarios for the post-2030 development agenda can be endlessly debated and put together in various ways, with the outcome far from certain. ECDPM has three basic and one more complex scenario, yet all need to be taken with more than a ‘pinch of salt’ and are certainly works in progress. With the current unprecedented global volatility, scenarios aremore ‘food for thought’ than reliable prediction. Europe would have an interest in influencing any scenario, yet if it is divided and distracted and does not reach out then scenarios one or two are much more likely. If it wants to be a player in scenario three or the hybrid scenario four this requires positioning and some political engagement not indifference.

Three basic scenarios

One complex hybrid scenario

The cost of the lack of investment for Europe

The true cost of Europe disengaging from a future global sustainable development framework needs to be spelt out in geopolitical as well as development terms. Framed narrowly around values or solidarity, European political interest and sponsorship will remain limited. Yet disinterest would carry real strategic and political consequences.

A world without a credible global framework, or one shaped without meaningful European engagement, would not be neutral. It could accelerate the shift towards narrow, self-interested, sovereignty-first models, where cooperation is transactional and global challenges are addressed selectively. Europe would increasingly respond to priorities and framing defined elsewhere, often at higher cost and with less influence.

The dividend and return on investment from engagement in post-2030 may not be immediate, but it signals commitment to dialogue, joint global problem-solving and defining shared priorities, rather than narrow self-interest. A future framework could influence priorities on climate action, digital transformation, food security, governance, industrialisation and reducing inequalities, all central concerns for Europeans and its partners.

If undertaken ambitiously, and in a spirit of co-creation rather than prescription, it could also help reset the EU’s relations with much of the Global South.

Yet if Europe is to be a player then some things need to happen fast in 2026:

-

Connect a post-2030 sustainable development agenda with citizens interests and politics inside Europe.The future agenda should be relevant to the cost of living crisis, housing issues, decent work, digitalisation, demographic change, industrialisation and inequality issues within Europe if it is going to resonate with the public and politicians.

-

Engage globally with humility and openness to forge pragmatic alliances. This includes different types of alliances with middle powers, new polls of influence and established UN groupings. The idea that Europe alone can set an agenda was fantasy in a previous era but certainly is now doubling the need to reach out pragmatically. Co-creation not faux consultation will be needed.

-

Plan and demand that European official actors coordinate among themselves better. Meaningful collective European action is in short supply but collective thinking and action will need to be forged in 2026 from the technical, diplomatic and political level.

-

Invest in and utilise science, innovation and evidence for international dialogue and the content of a post 2030 Agenda. This will help provide a basis for discussion within and beyond Europe… care should be taken that it is not so technical that it is impenetrable to wider audiences but knowledge can help bridge divides and connect in ways that traditional diplomacy struggles.

To be fair, at the technical level, Europe is beginning to do some homework on the post-2030 agenda. Amongst a number of knowledge institute initiatives, ECDPM was, for example, invited to provide input to the Austrian SDG Forum at the request of the Austrian Ministry of European and International Affairs in 2025. The past Danish Presidency of Council of the EU also invited ECDPM to present to the Council of the European Union’s Agenda 2030 working group in November 2025. Also, the European Think Tank Group, which ECDPM is part of, has also begun some first reflections amongst its members with the goal of feeding European policy makers and also reaching out to others.

There is now endless commentary on the changing world, and within the EU a significant concern about the place of Europe within this. Negotiating a framework for common dialogue and global goals, even with all its many difficulties and inevitable flaws, is not a luxury but a necessity.

Finally, if you are already working on the post-2030 Sustainable Development Agenda, in Europe or globally, ECDPM would very much like to hear from you. Contact Andrew Sherriff at as@ecdpm.org.

The views are those of the authors and not necessarily those of ECDPM.