AUDA-NEPAD: Does money and focus equal ownership and trade?

With trading having officially started under the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) on 1 January 2021, the African Union (AU) and its member states are now under pressure to make this agreement a success. But as analysis of the agreement shows, most gains are not expected from tariff reduction but rather from reducing non-tariff barriers and from trade facilitation – where improving trade-related infrastructures is key.

The best laid continental plans…

The AU has a continental plan covering trade-related infrastructures too – the Programme for Infrastructure Development in Africa (PIDA) was set up in 2012 precisely to help boost regional and continental infrastructure connections. It laid out a framework of ‘priority’ projects – a shortlist from country and regional submissions – which needed funding.

Past analyses frequently cite a financing gap of $93bn per year for African infrastructure. With a more ambitious development goal in mind than the World Bank’s calculations, the African Development Bank (AfDB) estimated in 2018 that $130-170 billion per year are needed to achieve universal access to power and water, extended ICT coverage, and improved transport infrastructure by 2025, while current commitments still leave a financing gap of $68–$108 billion annually.

Despite some progress, the first generation of PIDA was not a roaring success. Africa still lacks the necessary infrastructure to trade efficiently on the continent. Under NEPAD, the agency set up in the early 2000s as a ‘new’ effort to promote an ‘African renaissance’, the first generation of the PIDA priority action plan (PIDA-PAP1) saw only mitigated success.

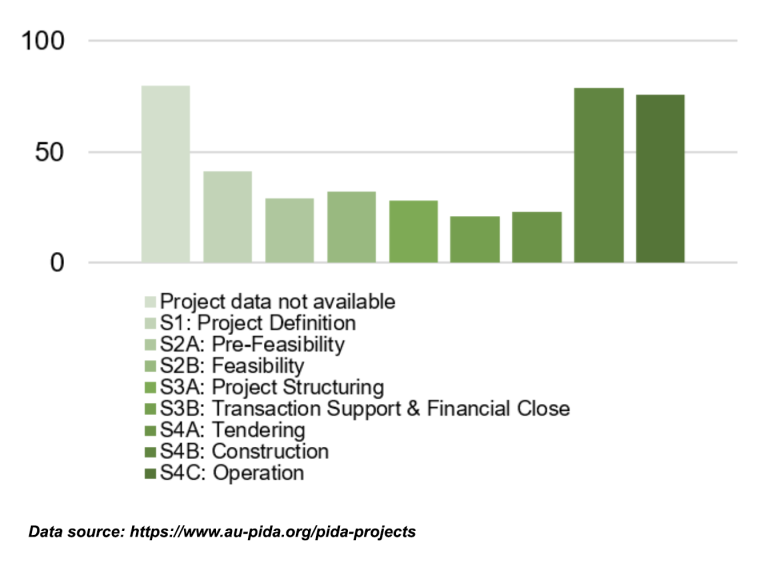

Figure 1 below shows that though 76 projects successfully came to full operation (the last bar on the chart), another 333 identified by AU member states as priority projects in 2012 are still at various stages of project preparation – some are indeed still at the phase of project definition, which precedes ‘pre-feasibility’ work. This slow progress highlights a key challenge that will remain going forward: member states and regional economic communities (RECs) have a much stronger role in implementation of these projects than in other policy areas where the AU is active.

But neither was PIDA a failure. It helped pool and channel funding to help set up numerous One Stop Border Posts (such as that between Rwanda and Tanzania or between Benin and Nigeria), upgrade ports (such as in Kribi in Cameroon or port access in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania), build cross-border roads (such as the Libreville-Brazzaville Road and the railway line linking Malawi and Mozambique), and lay fibre-optic cables across the continent.

AU reforms, new NEPAD

In the meantime, a set of wider reforms have been implemented at the AU, stemming from the influential Kagame Report of 2017. These include measures to improve self-financing, increase the focus of the AUC in the name of efficiency and effectiveness, better define the division of labour between AU structures, and ways to improve AUC management and recruitment.

But on top of that, the report proposed a reform of NEPAD into the AU Development Agency (AUDA-NEPAD). That transformation speaks to the spirit of defining a better division of labour: while the AU Commission Department of Trade and the AfCFTA Secretariat are to work on the policy side and the ongoing negotiations of the AfCFTA agreement, and the AU Department of Infrastructure and Energy is responsible for overseeing the PIDA framework, AUDA-NEPAD has an implementation-oriented mandate. That makes it a leader for ‘hard’ infrastructure development in Africa.

Successful implementation of PIDA Priority Action Plan 2 in support of the AfCFTA therefore presents a one-of-a-kind test for AUDA-NEPAD to demonstrate its effectiveness in carrying out this new mandate. The second generation of PIDA is conceived as a more realistic package of infrastructure projects. The need for trade-enhancing infrastructure, for example efficient transit corridors spanning several countries, is immense.

At the AU summit in February 2021, the assembly confirmed the new generation of PIDA projects, previously approved by member states’ ministers in the Specialised Technical Committee on Transport, Transcontinental and Interregional Infrastructure, Energy and Tourism. Fifty completely new infrastructure projects were selected to “focus on key priorities with continental scope”, ten from each of the five geographical regions, with at least one per sector from transport, energy, ICT and water. With this cut in the number of projects, AUDA-NEPAD is arguably applying the impetus of the AU reform to focus, while balancing this with regional representation.

Increased member state ownership?

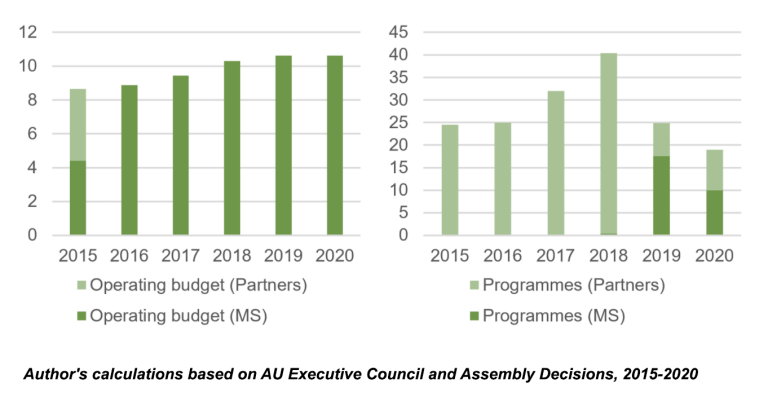

The transformed AUDA-NEPAD has matured from an initiative underpinned by its initiating countries – Algeria, Egypt, Nigeria, Senegal, South Africa – to a fully integrated AU organ. This means that member state contributions to the AUDA-NEPAD budget have increased. As Figure 2 shows, member state contributions now fully cover the operating budget, while they have gone from no programme support to financing about half of the programme budget in the last two years.

Whereas NEPAD was financed and governed by its initiating countries in its early days, it is now therefore financed by all member states through the AU‘s scale of assessment. This is a sea-change from NEPAD’s earlier challenges, as previously identified in 2017. As foreseen by the Kagame Report for the AU as a whole, greater member state participation may stimulate greater interest and ownership of the AUDA-NEPAD agenda. Combined with specific champions, for example through the Presidential Infrastructure Champion Initiative, together these reforms may help overcome some of the ‘political, governance and technical challenges’ faced in the past.

While keeping member states in the driving seat through their role in the budget, AUDA-NEPAD is also preparing to receive more funds from other partners and new sources. After a decade of only a handful but strong partnerships, AUDA-NEPAD plans to introduce the AU Development Fund (AUDF) in recognition that the “annual assessment of the member states will not be adequate to meet the funding requirements of the AUDA-NEPAD”. A planned AU Infrastructure Fund is to mobilise resources from sovereign wealth funds and pension funds in Africa, in the spirit of AUDA-NEPAD’s 5 Percent Agenda seeking greater contributions from African institutional investors.

Infrastructure: the key to AUDA-NEPAD jumpstarting the AfCFTA

While this seems to bode well, and AUDA-NEPAD’s regional conceptual Integrated Corridor Approach offers a useful framework to provide added regional value, the reality is that the buck still stops with individual member states. A look at the Maputo Development Corridor shows that while regional and continental frameworks can help, and the new implementation-focused AUDA-NEPAD can support, ultimate success depends on quite specific combinations of timing, people and interests – it responds to a political need or ‘problem’.

While PIDA provides a useful framework for building regional value chains with frictionless trade, fast customs procedures and cost-efficient multi-modal transit corridors to make trade through the AfCFTA a reality, AUDA-NEPAD can help, but ultimately success will come down to the key actors and interests around these at the country level.

Ueli Staeger is a PhD candidate in International Relations/Political Science at the Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies, Geneva. He currently researches how international organisations shape the provision of security, with a focus on the African Union, and the resource mobilisation relationships of international organisations with member states and external partners. In his doctoral dissertation, different case studies explore the African Union’s resource mobilisation in its programme budget, peace and security and infrastructure development.

The views are those of the authors and not necessarily those of ECDPM.