Europe's response to violent conflict: Shifting priorities in a changing world?

The world is undergoing major changes: how is Europe adapting to these in the field of peacebuilding? Blog and interviews.

There is an ominous sense of change going through Europe and the rest of the world. Brexit, the rise of Euroscepticism, the Trump presidency, high-profile terrorist incidents in Europe, violent conflicts coming closer to Europe’s borders together with the most significant refugee crisis since the Second World War have all clearly played their part. What is less clear, however, is the impact that these events are having on effective responses to violent conflicts and more generally on the support for sustainable peacebuilding.

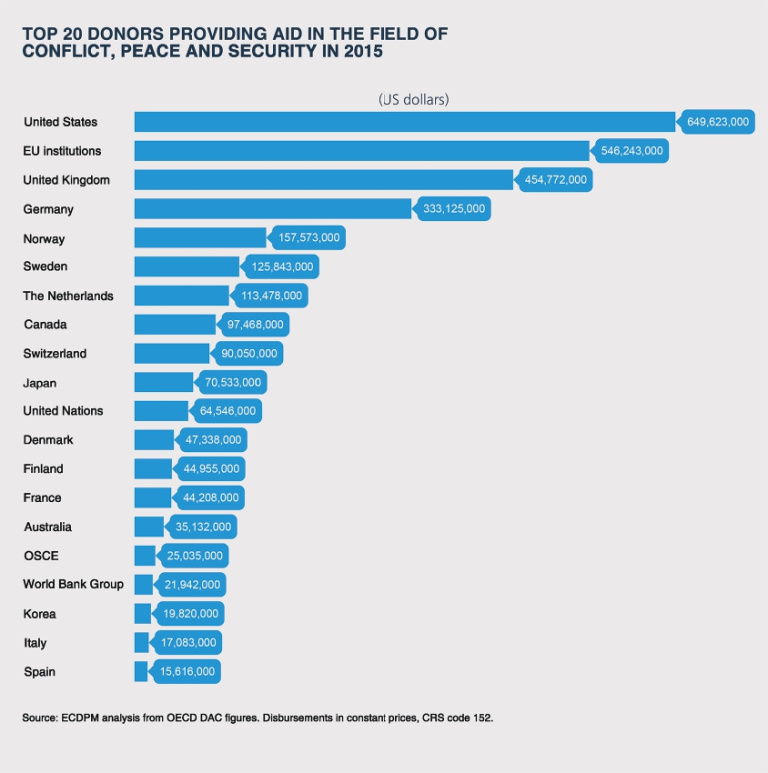

The EU institutions and a select group of EU member states are amongst the biggest supporters of peacebuilding. They represent five out of the top ten donors for aid devoted to conflict, peace, and security. Yet, it is not only money but political and policy support that matters and disruptive changes could be of global significance.

Global trends

Since the end of the Cold War, policy and financial support to peacebuilding have risen substantially because of the increasing political desire to undertake and support this type of work. Indeed, in the last 30 years peacebuilding has gone from being an obscure academic term referenced in the UN Secretary-General’s 1992 “Agenda for Peace” to being mainstreamed into many European foreign and development policy commitments. Peacebuilding has moved from being considered a set of distinct activities to a comprehensive, integrated or strategic approach in settings affected or potentially affected by violent conflict.

Some practitioners, however, have criticised using ‘peacebuilding’ as a blanket term that includes all efforts to end conflict and rebuild peace. Actions undertaken by non-governmental organisations and those carried out by governments and multilateral organisations, including military missions, are very different in nature and intent. Plus, the lack of “conflict sensitivity” of activities undertaken in areas susceptible to violent conflict is seen as increasingly problematic. Also the absence of a shared vision of what peacebuilding really means, who does it, how, and why it is clearly a major challenge for effective response.

These questions are all the more relevant when terms such as crisis management, resilience, stabilisation, countering violent extremism and addressing ‘root causes’ of migration are increasingly used in the policy discourse in Europe when talking about responses to violent conflict. Also ‘conflict prevention’ is a term currently championed by the new UN Secretary-General. All these terms seem to appeal domestic and policy constituencies in Europe more than ‘peacebuilding’ currently does. They are elements of the several attempts to refresh policy frameworks in Europe to make them ‘fit for purpose’ in a changing world. For instance, the new European Consensus on Development was adopted on 19 May. While it recognises that ‘peacebuilding and statebuilding are essential for sustainable development and should take place at all levels, from global to local, and at all stages of the conflict cycle’, certain NGOs immediately condemned in their analysis its emphasis on the ‘securitisation’ agenda and migration management. According to the EU’s High Representative and Vice President Federica Mogherini, “the world has changed, the situation in the world has changed and we are adapting our policies to that”.

There is a constant pressure for results from European politicians when building peace has, in fact, become more complex. While violent conflict (both internal and international) has declined since the end of the Cold War, since 2014 there has been a worrying trend upwards, with conflicts rising to 50 in 2015 (the highest number since 1991). In 2016, one-third of global conflicts took place in Africa. As a consequence 2015 has been the year with the highest level ever recorded for forcibly displaced people (65.3 million people).

Europe’s evolving priorities

The European Union is promoting an “integrated” approach to conflict in the follow-up to its 2016 Global Strategy for Foreign and Security Policy. Germany will most likely launch new guidelines on crisis engagement and peacebuilding later this month, and the United Kingdom already has the 2015 National Security Strategy and Aid Policy where responding to conflict features significantly. Sweden’s new 2016 policy on development cooperation and humanitarian assistance significantly references peacebuilding, even more so than in 2013, but it also shows a strong focus on issues like migration. What these strategies have in common is that they all express the need to tackle the causes of instability, insecurity and conflict – both to reduce poverty and for European and national security reasons – as well as the importance of strengthening resilience, at home and abroad.

Beyond the rhetoric, some NGOs are worried about a securitisation of peacebuilding and fear that Europe might shift too much to a political and financial focus closer to its borders. The commitment or real spending of official development assistance (ODA) resources in conflict and fragile states is often increasing, with the EU institutions spending 43% in 2015 and the UK committed to allocating 50% of all DFID’s spending to fragile states and regions. Yet spending, ‘in’ conflict and fragile settings is not necessarily peacebuilding and may not even be ‘conflict-sensitive’ – it may cause more harm than good.

Larger changes in response to migration flows also have a knock-on effect on the support to development assistance, with possible consequences on peacebuilding. For instance, 33% of Swedish ODA was spent internally on refugee issues in 2015 and humanitarian spending has been taking up an increasingly large share of ODA budgets. In Germany, some funds have been re-allocated from broader peace and security objectives towards addressing migration. In 2016 migration has been added to one of the strategic objectives of the UK’s conflict, security and stability fund, a mechanism which has significantly financed peacebuilding in the past but which has also come under press criticism for some of its spending and lack of transparency. Similarly, a review of projects under the EU Trust Fund for Africa aiming to address root causes shows that while initial activities were strongly focused on resilience and employment projects, more recent programmes are putting a stronger emphasis on migration governance.

Investing in understanding change

To have a better picture of how these changes are impacting peacebuilding, ECDPM has therefore begun a project to look in more detail at the recent evolution of political and financial support. The focus is on the European Union institutions and three countries that have a longer history and significant past investment in peacebuilding, namely Germany, the UK and Sweden. ECDPM will be conducting qualitative and quantitative analysis throughout 2017 on this topic and welcomes inputs and insights from the practitioners and experts working on peace and security.

ECDPM’s project “The Changing Nature of European Support to Peacebuilding” is funded by Humanity United and ECDPM’s own resources.

What do the experts think?

In the first of a series of interviews for this project, ECDPM’s Andrew Sherriff asked two experts about the changing landscape of peacebuilding in Europe. Sonya Reines-Djivanides, Executive Director at the European Peacebuilding Liaison Office (EPLO) and Rory Keane, Head of the UN Liaison Office for Peace and Security in Brussels, answer three key questions.

The views expressed here are those of the authors and of the interviewees and not necessarily those of ECDPM.