How to anchor the Global Gateway strategy in local realities

Authors

Amandine Saboutin shows that local and regional authorities (LRAs) are already playing more roles in Global Gateway projects than is often recognised. Yet their engagement remains uneven.

As the EU’s Global Gateway moves from ambition to implementation, one crucial question arises: how can it deliver impact on the ground? Recent ECDPM research shows that local and regional authorities (LRAs) are already playing a more significant role in Global Gateway projects than is often recognised. Yet their engagement remains uneven, constrained by decentralisation gaps and limited political incentives at the national level. The Forum on Cities and Regions provides an opportunity to advance its agenda.

Over the past six months, ECDPM has done extensive research to understand how LRAs are involved in the implementation of the EU’s Global Gateway strategy. Building on our initial study on giving local authorities a voice and drawing on interviews with more than 40 EU delegations and a mapping of 46 concrete case studies across continents and sectors, the findings offer a unique snapshot of how Global Gateway is taking shape on the ground – and what role and opportunities there are for local and regional authorities. The Forum on Cities and Regions in International Partnerships, held on 8–10 December, is an opportunity to discuss these results and next steps.

The picture that emerges is both more dynamic and more nuanced than current policy debates often assume. Much of the existing discussion around Global Gateway focuses on scaling up investment efforts, boosting European interests and the private sector, the big-ticket flagships and the connectivity agenda – energy interconnectors, digital pathways, and major transport infrastructures.

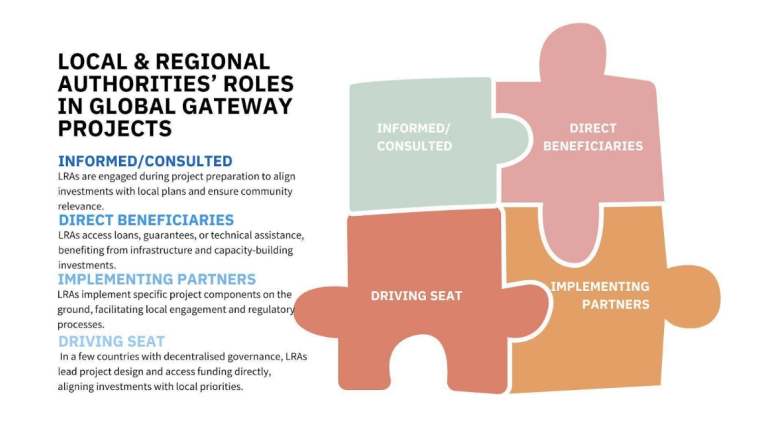

Yet our research shows that beyond these emblematic projects, a constellation of less visible, locally anchored initiatives is already connecting investments and LRAs. While all Global Gateway projects have a territorial dimension, the degree of local and regional authorities' involvement varies, depending on the nature of the project, its origin and the national decentralisation framework. As opposed to operating as demand originators, local and regional authorities play a range of roles: beneficiaries, implementing partners, and at times, they are even at the driving seat. In most cases, they are at least consulted and informed at the early stage of the project’s design.

Local and regional authorities are involved in a myriad of ways

The evidence confirms that LRAs are increasingly involved in Global Gateway projects – in ways that should not be overlooked and which make a case for stronger involvement. Some benefit from loans and guarantees, like in Morocco or Ecuador. Others are implementing partners on blending projects, like in Cameroon and Namibia.

Even in cases where they are not formal partners in a flagship initiative, local authorities frequently play critical roles in complementary or ‘satellite’ interventions under the Global Gateway’s ‘360-degree approach’. These range from climate-resilient urban planning linked to energy infrastructure, to digital governance initiatives supporting connectivity investments, to local service delivery reforms that strengthen the enabling environment for larger EU-backed pipelines.

Such projects generally ‘prepare the ground’ for larger infrastructure deals by improving local governance, building institutional capacity, reducing regulatory bottlenecks, and strengthening the territorial conditions that ultimately determine whether investments are sustainable and inclusive. In many countries, these ‘360-degree’ interventions, funded under NDICI-Global Europe, sometimes as part of Team Europe initiatives, are essential to ensuring that investments are directed to territories that can benefit from them. This is the case in Nepal and Indonesia, for instance.

But our research also clearly shows that much of the EU’s engagement predates the conceptualisation of Global Gateway investments and that these investments ‘enter’ an ecosystem of existing plans, strategies, coordination frameworks and actors – and in particular enter into a political equilibrium.

One clear finding from our investigation is that the EU delegations are already engaging with cities, regions, associations of local authorities and municipal enterprises not only on Global Gateway-labelled activities but across a much broader landscape of investment-related programmes. These interconnections are often informal or uncoordinated, yet they illustrate the depth of the EU’s existing territorial footprint and the potential to systematise and scale it. They also highlight the need for a thorough understanding of the political process of decentralisation, which is context-specific and may create bottlenecks.

Despite a lot of positive examples, LRAs’ engagement remains uneven and shaped by persistent structural constraints.

Structural bottlenecks still remain

Despite a lot of positive examples, LRAs’ engagement remains uneven and shaped by persistent structural constraints. Two in particular stand out.

First, national legal and policy frameworks on decentralisation remain a foundational bottleneck. In many countries, LRAs lack the mandate, fiscal autonomy or administrative powers to meaningfully influence investment planning or access investment instruments. In several contexts, in addition to limited resources and capacity, LRAs cannot borrow, provide guarantees or directly contract with international partners – as seen in many of the cases reviewed. Even where decentralisation laws exist on paper, implementation is often partial or nascent.

Second, central government political incentives frequently limit the depth of local involvement. Investment sectors such as energy, transport, water or digital connectivity are strategic domains where central authorities tend to retain control. Delegating influence or agency to local governments can be politically sensitive, disrupt established networks, or complicate centralised coordination of large investment pipelines. Without incentives aligned toward territorial inclusion, even technically strong LRAs face obstacles in shaping or benefiting from investments.

These bottlenecks require political, institutional and long-term solutions, which a comprehensive strategic approach to investments in partner countries should take into account, and eventually address.

Adaptation will be essential for the Global Gateway’s implementation

One important conclusion from the research is that Global Gateway remains a relatively young and evolving strategy, and stakeholders are getting progressively acquainted with the changing approach. Its investment pipelines, governance mechanisms and partnerships are still being consolidated. Learning curves, experimentation and uneven implementation are therefore not only expected but necessary.

Integrating LRAs meaningfully into investment processes takes time. It requires a strategic, tailored approach at the country level, where targeted technical assistance and institutional learning across sectors matter. It also depends on national reform trajectories that are beyond the EU’s direct control but can be part of the EU’s country strategy and policy dialogue.

Initial challenges can therefore be seen as part of an ongoing transition toward a more mature investment approach– one that recognises the territorial dimension as core to Global Gateway’s impact and sustainability.

If the EU is serious about ensuring the long-term, inclusive and territorial impact of Global Gateway investments, the next steps will require not only more evidence but above all the adoption of a coherent territorial strategy response. A comprehensive EU toolkit already exists, from budget support and blending to guarantees, technical assistance, peer-to-peer exchange and policy dialogue. But deploying these instruments strategically to address decentralisation bottlenecks, incentivise central-local collaboration, and empower local authorities requires clearer priorities and deliberate political choices.

The views are those of the authors and not necessarily those of ECDPM.