What the EU’s plans to phase out Russian gas mean for Europe and Africa

The war in Ukraine is redrawing the lines of the EU’s energy policies. It will be critical to retain an outward perspective and keep the momentum for renewable energy transition in Africa as well as in Europe. The war in Ukraine is changing Europe for good. The choices European leaders make today will define the collective security and stability of the EU. There are few areas in which the geopolitical tensions with Russia are as strong as in the EU’s energy policy. The EU gets roughly 40% of its natural gas from Russia. Kremlin threats to shut down the main pipeline to Germany are a major security concern, and Europe’s dependence on Russian gas directly funds the Russian government as it wages war against Europe.

“Bloody hard”

In an attempt to move quickly, the EU announced its plans to rapidly wean itself off Russian gas last week. The aptly named REPowerEU plan seeks to reduce Russian imports by two thirds by the end of the year. It proposes to replace an estimated 60 billion cubic metres of Russian gas with liquefied natural gas (LNG) and pipeline supplies from other parts of the world by the end of the year, front-load investment in renewable energy, and boost investment in cleaner gases (green hydrogen and biomethane).

In April, the EU will also propose legislation requiring storage facilities to be filled at least 90% by the next heating season. This means it will also come at a great cost, as prices are already at a record high and storage levels are low.

It is hard, bloody hard. But, it is possible, if we are willing to go further and faster than we have done before.

Despite calls from some EU member states to sanction Russian energy following the US oil and gas ban, several member states (including Germany) continue to reject an EU ban, confirming the leverage Russia has over the EU with its energy exports. At an informal meeting in Versailles on 10 and 11 March, EU leaders instead backed further measures to phase out Russian supply and cushion the blow for EU consumers.

African gas: close but hard to reach

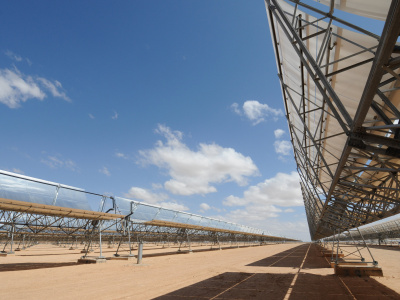

The REPowerEU plan proposes to increase imports from existing pipeline suppliers (Norway, Algeria and Azerbaijan) and LNG from the US, Qatar, Egypt and West Africa. Talks are ongoing with existing African suppliers, yet newer entrants like Tanzania have also expressed interest in supplying LNG to Europe. Shifting supply, however, is not done by the flick of a switch.

There is only limited potential to ramp up imports from Algeria without significant investment in production capacities. Nigerian gas requires new pipeline infrastructure across the Sahara, and LNG from a country like Tanzania requires new liquefaction infrastructure that is yet to be built. Current LNG suppliers like Egypt also tend to favour long-term contracts, and have focused more on Asian markets in recent years.

African gas therefore is unlikely to be a quick and easy fix for Europe’s supply problems. The long game for the EU’s energy security is still phasing out natural gas and rapidly electrifying household and industrial energy consumption. The EU is also unlikely to change its dismissive stance on financing (long-term) fossil fuel development abroad, which is a longstanding source of tension in the AU-EU partnership.

Front-loading renewables at home, backloading investment abroad?

The European Commission also intends to front-load a number of renewable energy investments at home, including plans to generate up to 15 terawatt hours of rooftop solar energy within a year, double the deployment of heat pump rollout and increase wind and solar deployment by 20%. For utility-scale renewables it will also seek to accelerate deployment through fast permitting of renewable energy projects. This shows that renewable energy is now firmly seen as a European security issue, warranting extraordinary measures.

(...) affordability, sustainability and security concerns ultimately have the same answer: the Green Deal

As the EU accelerates its transition at home, the question is whether it will be able to do so without jeopardising its ambitious plans for renewable energy and infrastructure abroad. The EU’s €150 billion investment package for Africa, which it presented just days before the invasion, relies to a large extent on projected private finance. European energy companies and investors active in Africa may now turn towards the European market first, which risks African countries drawing the short end of the stick twice.

A more inward-looking approach to renewable energy transition would risk deflating the limited momentum the EU has been able to create with its African partners around a just and equitable energy transition. This would be bad for the climate, but also bad for diplomacy, and set the AU-EU partnership back a number of years.

The EU is rethinking the pace of its own transition in the face of crisis and taking extraordinary measures to undo Europe’s risky dependence on Russia. This is an opportunity to develop a new form of energy partnerships with its southern neighbours, built on structural interdependence and mutual benefits. This requires stronger EU Green Deal diplomacy, faster deployment of renewable energy and green hydrogen production, and interconnections with Africa, but also investing in sustainable and low-carbon industries that can be the backbone of an interconnected green economy between Europe and key (North) African countries.

The views are those of the author and not necessarily those of ECDPM.